When I first proposed this topic, I figured I’d take a Bible-thumping, fundamentalist position. But as I thought about it, I realized I can’t do it justice and will probably come off as a caricature. Besides, I really do “accept the Holy Scriptures, the Old and New Testaments, as the word of God and the only perfect rule for faith, doctrine, and conduct”. As John Piper put it, “Everybody to my left thinks I am [a fundamentalist]. And there are a lot of people to my left.” Where I diverge from fundamentalism is not in my confidence in the Bible, but rather in my confidence in my interpretations of it. That’s why I spend so much time on Biblical Hermeneutics.

The Evangelical tradition traces it’s roots through the Reformation, which paralleled the Cartesian movement in science. Just as modern science rejects the traditions handed down from our ancestors, Luther and his spiritual children rejected the traditions of the Roman Catholic church. Since Catholics lay claim to apostolic succession, it’s natural to assume Protestants abandoned our connection to Jesus’ followers through the ages. That is not the case.

More accurately the Reformation (and the early moderns in general) sought to discover first principles using new techniques. Innovations in literacy, translation, and publication allowed more people to read and understand the historical sources of Christianity. Globalization (round one) put ordinary folks in contact with the huge array of belief systems: Christian and otherwise. Political winds shifted toward rudimentary democracy as ancient Greek and Roman texts were rediscovered. In short, people began examining the world around them with a more critical eye.

When the Reformers looked at the church, they were troubled by what they saw. It did not seem to conform to the picture Paul painted:

But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he himself is our peace, who has made us both one and has broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility by abolishing the law of commandments expressed in ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross, thereby killing the hostility. And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near. For through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father. So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone, in whom the whole structure, being joined together, grows into a holy temple in the Lord. In him you also are being built together into a dwelling place for God by the Spirit.—Ephesians 2:13-22 (ESV)

What they saw wasn’t one church built on the foundation of Christ, but two churches at war with one another. In the earthy glory of the public face of Christianity, it was difficult to see the surpassing glory of its founder. Each branch of the church claimed the Holy Spirit was directing them to build strikingly different dwelling places for God. Something had gone wrong and it was time to peel back the layers and find our firm foundation.

At this moment, our master bedroom doesn’t have a door. When we repainted, we decided to replace our boring flat door with a fancier door that’s less beat up. As I drilled the last hole and screwed the last screw to attach the hinges, I discovered that it didn’t close all the way. To fully illustrate my ineptitude, it doesn’t open all the way either. So I had a choice: I could fix my mistake or I could play out an episode of Home Improvement and “fix” the door frame.

At some point in the past, the Catholic Church made a few small mistakes in laying out their floor plan. It happens; we’re human. When you make a mistake, you need to fix it as quickly as possible to avoid problems down the line. But that gets tricky when the Pope speaks ex cathedra. It gets even more complex when other branches of the church claim other sources of authority. You don’t solve this sort of problem by ignoring it and continuing to build.

Reading Paul’s letters to early churches, I’m struck by how often he appeals to the witnesses of Christ’s life, death and resurrection: the apostles. The church must be “built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone”. His readers would have known that “the prophets” were the third leg of the Tanakh: the Jewish Scriptures defined by the Pharisees. All that remained of the men, who foretold of a coming King of the Jews who would put things right between God and humanity, was their writings that had been carefully preserved.

Meanwhile, Paul’s first readers had probably heard of Christ via eyewitnesses who were scattered by persecutions in Jerusalem and the surrounding country. (Ironically, Paul himself was one of the reasons the message of Christianity spread to Gentile regions—first because he harassed followers of The Way and later because he was commissioned on the road to Damascus to preach to the Gentiles.) To them, “the apostles” were people, not writings. But within a few years, Mark and Luke saw a need to start recording the memoirs and acts of the apostles so that they would be preserved for future generations. Soon other writers began publishing accounts of Jesus under the Gospel classification. What began as an oral foundation, quickly emerged as a corpus of written material.

By the end of the second and start of the third generation of the church, all of the New Testament texts had been written, though nobody called them that yet. Other Christian writings also survive from that time, but they were a trickle compared to the explosion of written output that began in the second century. Meanwhile, various theologies were proposed and propagated at the same time. It shouldn’t be a surprise as the apostles themselves dealt with theological controversies. For the average Christian, who grew up in a polytheist culture, it must have been confusing and overwhelming.

Perhaps more than anyone else, we can thank Irenaeus of Lyons for clearing up the orthodox position. He particularly addressed the Gnostic thinkers and writers who believed that Jesus had passed “secret knowledge” to His closest followers. In response, Irenaeus points to the writings of the apostles, who were Jesus’ companions on earth, and those who learned the gospel at the apostles’ feet. If the disciples of Jesus taught publicly what He Himself taught them, they weren’t keeping His knowledge secret! Analysis of Irenaeus’ Adversus Haereses shows that he considered John’s Revelation and letters, Paul’s letters and Luke’s history of the first generation of the church to be authentic. More importantly, he made an explicit case for the four (and only four) canonical gospels. It would be a few hundred more years before the New Testament was finalized, but it’s shape was clearly outlined by Irenaeus.

Irenaeus also noted that none of the bishops of the major Christian centers espoused the Gnostic heresy. So oddly one man substantially contributed both to the theory of Episcopal polity and Sola Scriptura. But when you get right down to it, why not? At that point in history, the leaders of the church had over and over again come down on the side of the apostolic teaching found in the Gospels. The phenomena is easy to explain: they recognized the authentic Jesus taught to them by their spiritual parents in the biographies of the fourfold Gospel. Other accounts of Jesus’ life, many of which were written to justify Gnostic teaching, did not look like the person they acknowledged as their Lord.

So we can thank our common tradition, the fathers of the church, for recognizing, compiling and preserving the teachings of the apostles. As we read in Luke’s account of the apostles activities, they were filled with the Holy Spirit as they wrote our New Testament just as the prophets were filled with God’s Spirit when they wrote the Old Testament. The Holy Spirit gives us the assurance that the Scripture is reliable, but He doesn’t do His work along. He always uses the Church to perform His good works, which is how tradition gave us our Bible.

Filed under Uncategorized

Tagged: Bible, Evangelical

I’d just like to take a second to put in another plug for Biblical Hermeneuitics if WordPress will be so kind as to accept my non-spammy link I’d greatly appreciate it; it really is a great site.

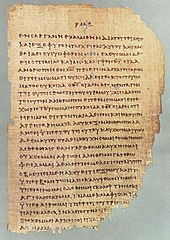

Fascinated by this image and the architecture….but no insight is given on where it is or why it is relevant to the text can Jon Ericson help. It is the twin towered structure at the top of your post on how tradition gave us our bible…..completely agnostic but several buildings (or more accurately “follies”) like this in my region….Hope YOU CAN SHED SOME LIGHT ON IT